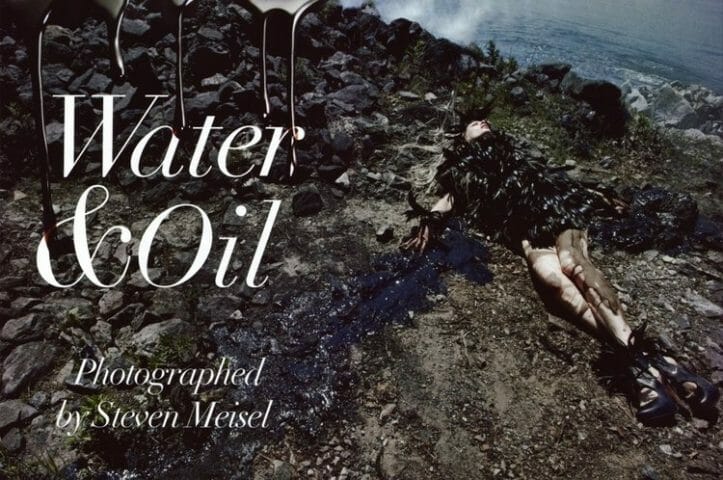

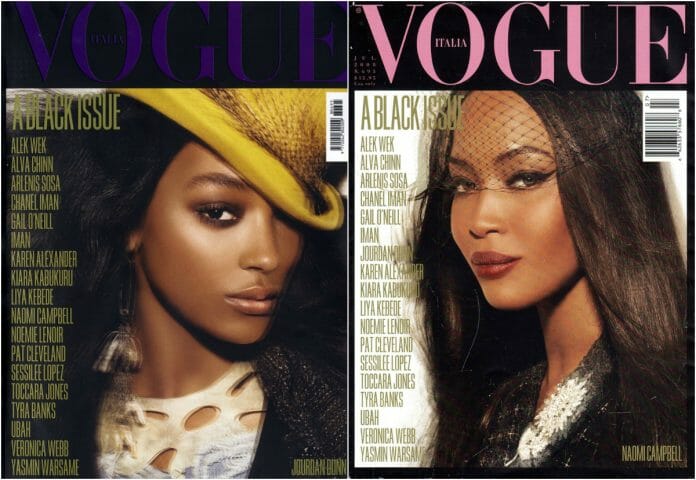

I grew up under the influence of Vogue Italia. Franca Sozzani changed fashion imagery by exploring and expressing more than beauty. This revolutionized the Vogues‘ aesthetic, many of whose photographs and images, since Sozzani, are controversially described as “art”.

Franca had what Joan Didion calls “a predilection for the extreme”. Seemingly fearless, she expressed ethics no one else would touch, with full force: Blackness, fat, ecological disaster, domestic violence, plastic surgery. And, in what should be a lesson to us all, she was not fired. She remained editor of Vogue Italia from 1988 until her death in in 2016. She says that what she’s proud of is that she was able to communicate –from a country whose verbal language is not widely shared– global issues to a global audience, using images.

I met Franca formally through Netlix documentary program, which has led me stumbling through my own formative influences: Evel Knievel, David Bowie, Jeremiah Tower, Manolo Blahnik, and Harvey Milk, as well as Joan Didion, Tower Records, and other fierce presences in the California landscape, who I relate to with the combination of certainty and blur that characterizes childhood memory.

The piles of Vogue magazines in our home taught me an avant-garde aesthetic, but I didn’t know it at the time. My mother’s conventional English chintz décor and the magazines’ gloss and commercialism suggested I was looking at the cultural center, not at any sort of questionable fringe.

My mother’s fashion reflected her work traveling to Europe to select clothing from the couture shows and track down authentic antiques for her superrich clients. I don’t recall seeing her in anything but an Yves St. Laurent suit or a client’s castoff full-length formal evening gown.

My idea of “normal” was that everything must be high quality, rare, and, moreover have something to say. I was not exposed to conformity. But no one told me that any of this was special. To be a person meant to make these distinctions and establish an expressive personal style like no one else. When I dressed in accord as a young teenager, I was described by the prim rich kids with whom I went to school with the only language they had for this weirdness: “a slut”. This was totally bewildering.

I was so concentrated on keeping those massive shoulder pads in place and walking properly in those 13cm flourescent stilettos, that I didn’t notice that no one else seemed to be playing this game.

• • •

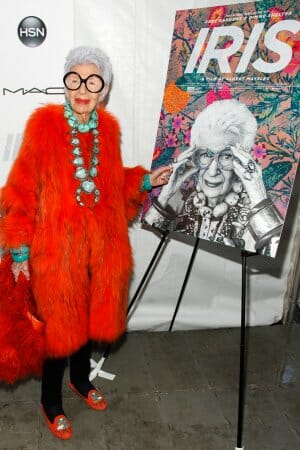

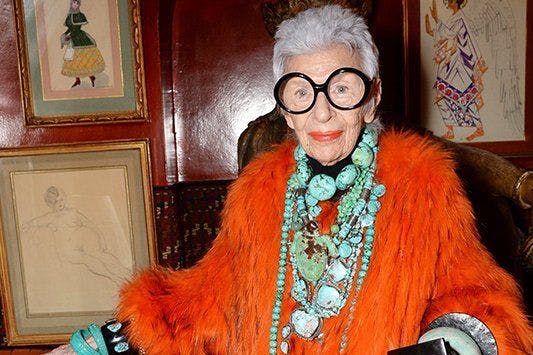

I remember someone saying to me a long time ago “some people look better naked and some people look better dressed”. I am the latter. The only thing that looks worse than naked is tight clothes. Of course loose clothes don’t look good when you dance tango in them. Without a bodice, we look “pregnant”. And as a teacher, I need people to be able to see my body. (I don’t understand why the male maestros don’t feel responsible to wear leggings or shorts so the students can see their leg joints properly). Tango campaigns against the sculptural, architectural clothing that comforts, pleases, and interests me (and my favorite Buenos Aires designer, Min Agostini). As a tango dancer, I have not been graced with the right body or the right beauty. Of course, I want to be the tango princess, with the skinny legs and the delicate shoes (I don’t want that boring hair!). My attempts at tango princess generally produce something I call “little fat fairy”. And while I know that –and “Unicorn”– is a perfectly respectable self-identity these days, it’s not mine. I am only interested in trying to be humorous in text. Anyway, my tango identity is angel, not fairy. Regardless, I’m driven to create images that express my ethics, costumes which say something. This comes at the cost of traditional beauty. And in practice, my attention to the logistics and aesthetics of our shows and shoots always seems to leave no time for me to primp my hair and makeup or refine my own costume from every angle. And there are still dreadful aesthetic flaws in my dancing, that no one seems to understand or fix and may be simply the detritus of ski racing and life as an athlete: too much muscle. I’m so tired of seeing myself not-beautiful in the resulting videos that while sketching our next two art videos, I considered removing myself from dancer to director, replacing myself with the perfectly beautiful and skinny Jessica Phoenix. Netflix soldiers on. In the early 2000s, Iris Apfel was discovered as a fashion icon for her unique assemblies of clothing and accessories and became, in her 80s, “a starlet”. At 97, she is still confident that she’s never been beautiful, but she still has something to say through her embodied style. This something is described in Buenos Aires as “demaciado”, too much, which was often the reception I received from my teachers, clicking their tongues and shaking their heads, when I would arrive at the party of the week, the DNI Saturday practica, in something I thought was a sassy combination of beauty and celebration. I think people underestimate the chutzpa it takes to wear extreme fashion. I have always had my aesthetic and I have never really been able to smash it into presentability, but I’ve also never gained confidence in it, because I have been persistently, since my teens, in one language or another, called “demaciado”. And this is not in the end about something superficial. The character that it takes to hang over the edge for decades is more helpless than resolute. We don’t know another way. This, I learned, is the meaning of “Avant-Garde”. And this “too much” runs deep. In the documentary, her son, the director, asks Franca if she ever failed at anything. He asks her repeatedly. The answer seems to be relationships. She says “people are attracted, but then they find out it’s too much.” This is a dogged theme in The Avant-Garde Diaries, an uneven series which reveals the compulsion to explain what you see and the attendant loneliness of being mostly misundertood. (My favorites episodes are https://vimeo.com/37613081, https://vimeo.com/41122282, https://vimeo.com/45856180, https://vimeo.com/46288545, https://vimeo.com/85763073) But this is not supposed to be another post about that, but a post about Vogue, about the idea that popular culture, at its glossiest, can also be a language for expression both profound and ethical, if we dare.• • •

That is a slick last line to a post. But what is (as my teacher Avery Gordon used to always ask) “the constitutive element” of daring? It is understanding that there is a cost. And too many people around seem to think that unconventionality is a delightful celebrity experience. It is not. It is a heavy expense, a burden and responsibility that I cannot free myself of. An exile and isolation. Without rationality, without trial, in the strange silence that has surrounded my productions as an adult, without it seems my having ever made a single choice in the main directions of the matter, beyond the one to continue living and walking one step at a time through this experience, with the intention to do my best, whatever that is.

I do not dance and teach the way I do because I “like to be different”. I do what I do because it seems like the right thing to do. It seems right to dance with a contemporary perspective on gender and sexuality and to present tango in contemporary aesthetics of athleticism, fashion, and music.Italian Vogue

Iris Apfel

Min Agostini