I went to Italy to eat tortelli, not to dance.

I am immediately disoriented. Everything looks, and smells, like Buenos Aires. The hallway of the apartment, a delicate mustiness. The smell of marble.

I arrive in the dark in a foreign land, Modena. There is a milonga nearby. I feel an old, now-unfamiliar, excitement. I change my clothes and go to find my people. In the park, the dance floor is surrounded with gravel and lit with security floodlights. There is no bar. I must join the “association” in order to dance, so now I have an official membership card to tango. Sneakers would make a lot more sense for traversing the dusty rocks between the tables and the dance floor and for not destroying one’s shoes on the rough stone floor, but it’s clear that my stilettos and rhinestones are indispensable, although we sit on rough crates that could destroy a fine dress.

Afterwards, I need a glass of wine to put my spine back in order. I’m sure to find a bar near my place in the center. But at 01:00 (Friday night) they are all absolutely and very closed.

Saturday morning I awake to glass recycling, followed by violin. I go out to buy Parmiggiano Reggiano. Before I can even arrive to the Mercato Albinelli, I am accosted with “Libertango”, followed closely by “Por Una Cabeza”, played by an tight eastern European trio who don’t react to any word I use in English, Italian, or Spanish, including the word ‘tango’. (Later we connect verbosely in Ukranian through googletranslate.)

At the deservedly famous Bar Schiavoni I eat a sandwich which is a revelation on the genre. The bread melts in the mouth. It’s not filling. And no single flavor dominates. Everything in that sandwich collaborates on delicate comfort. Every day, the list of 5 sandwiches changes according to the owners’ improvisation, which might be a way to keep the joy in hard work. And I eat here every day.

Of course, with the sandwich, Lambrusco, the local wine, sparkling from light pink to dark red, and good with every food or none. Now I understand. If you start drinking at 13:00, you have had enough by 01:00.

I buy 9 kinds of cheese. I go to the fabulous Gallerie Estense, finding that Italian art (even religious art) is full of subtle references and jokes, like tango’s adornos and like tango’s delightful shift of mood, from drama to humor.

On Saturday night the entire town becomes a street party hosted by “The Comune” (city government), with live music or loudspeakers at most restaurants, LED balloons, roving brass bands. At 01:00 the people go quietly home, leaving not a single piece of trash in the streets.

I realize that the Argentine chest is not Italian. Here, the shoulders are curved and the chest is sunken. This applies to every man and woman I see at tango and in the street. Apparently a chest is something you need in the New World, not the Old. French male posture is similar to Italian. Germans too sink the chest (without bothering to curve the shoulders) and additionally sink the hips forward and the belly out. No need at all for a proud posture. Whereas, in the US, Australia, New Zealand, and certainly Argentina, one must confront the situation with heart, and one must show oneself. There is no getting by on your brain alone. It seems that the Italian women do not feel the need to show cleavage. Although they dress up a lot, with sparkles from head to toe, again the chest is not shown. The situation here is just not so urgent. People are not in the spirit of fighting themselves and nature to survive and actualize themselves.

The old world is about entitlement. The new world is about competition. For which you need to be ready, with your chest.

The old world attached dignity to obligations. The new world bestowed it on posture and performance.

The old world survived by tribute. The new world by talent.

The old world understood sovereignty, grace, a sense of history, and a sense of responsibility. The new world understands independence and individualism.

New world and old world, if anything useful, are perspectives. Ways to reflect on how we are doing what we are doing. With a deep understanding of history and tradition carefully integrated with meaningful innovation (not destructive, egoistic innovation).

There is an old world of tango, and a new world. The old world was about old men and young men, and the girls who eluded them. The new world is about competitions, a dessicated “elegance“, and, above-all, marketing “authenticity“.

In Modena something happened which hasn’t happened since I was a beginner in Los Angeles and Buenos Aires. I danced with masterful old men. They also had the confidence and grace to compliment me afterward. (The young men are too insecure to acknowledge anyone else’s skills.) In København there is a milonga which doesn’t allow anyone to participate who is over 30, what a travesty of this intergenerational tradition.

Travel tips

“Italian” in the USA is a signifier for candlelight and romance.

I come to Italy to dress up elegantly, eat undegraded food in a spirit of reverence, and dance in ancient, candlelit rooms.

I do not pay good money to do or eat anything under this sort of lighting.

I accept that there is some other lesson, some other Italy, who has something to say to me. Not the one I came for. One I do not imagine.

The cycle of temperature and humidity not only dictate the process of the balsamico, but also the process of the day. I feel the tendrils of heat creep in, and as they do the sounds of the city recede. Then as the breath of the afternoon returns, slowly the sounds of life as well. This surrender to nature has a certain beauty, and perhaps it explains, psychologically, the surrender to the industrialization of food. Or surrender to life. Surrender to the ravages of the global economy.

Basically, the educated and talented Italians have surrendered by leaving. And left their country to crumble.

Every Italian is proud, especially of their home town, especially of the food. And yet that pride does not form vigilance. And like the almost imperceptible arrival of the heat of the day, industrialization is devastating.

Europe has been, frankly disappointing. I did not expect supermarkets, frivolous use of cars, timidity and fear, helplessness, surrender.

Here’s a tip: If you visit Italy, do not go for “a weekend”. Everything good is closed on Sundays. By definition, if it is open, it is for tourists. They may be Italian tourists, but still tourists. 70% of everything (and all the good restaurants) are also closed on Monday. Prescription: Arrive on Tuesday, go home on Saturday.

It’s Sunday. A rather virtuosic pianist plays difficult pieces in the Piazza below my window. I try to go to dinner. Repeatedly foiled, I wander home, wondering how I so often manage to go hungry in Italy, noticing that today the streets are again full of live music, but it is acoustic and wistful not party music. I get lost. I arrive at the Palazzo Ducale, where on the Piazza large loudspeakers distort under the pressure of 30 dancers in historical regalia. The man next to me explains it’s a demonstration of partner dances of the 1800s, beginning with the dance the soldiers learned for flirting with girls (but, he adds, the marriages were already arranged, so it was a farce). The subsequent dance was from 1850, the Mazurka. I’m standing in very hot sun, and I have chills. It’s tango. There’s plancha, cabeceo, the most popular of all tango jumps, and the one-sided embrace. 1850. Italy. Tango is not only African, it is also Italian. Wikipedia claims the Mazurka is entirely Polish, with some adoption across Europe but no mention of Italy. (Apparently it’s also the base of balfolk and zouk.) The demonstration proceeds to the vals from Verdi’s “La Traviata”, also performed in Italy in the 1850s. The announcer described it as the first image in Italy of a French style of dance. Of course, the embrace.

Somewhere between fantasy and reality

I am invited to dinner by a dancer born and having lived his whole life in Modena. It’s Monday. He cannot identify an open restaurant. We go to La Lambruscheria, whose owner serves us a Lambrusco with a flavor as light as the color is dark and recommends a restaurant which has no tourists in it. The outdoor seating is in a covered deck, with overhead lighting, and urinal smell drifting in. I watch the 2 mature couples at the adjoining table eating “gnocchi fritti”. I’ve learned by now that it has nothing to do with gnocchi. It’s fried layered bread, puffy when fresh, eaten either for breakfast plain with coffee or, at dinner, used to make small sandwiches by hand at the table, with proscuitto, and possibly some sauces/dips, accompanied by raw carrot and celery sticks and cherry tomatoes. One of the women asks a lot of questions about the sauces to her dining companion. I ask mine “are they from another part of Italy so they are just learning about this food?” He listened to the voices “no, they are from Modena. But they are receiving it with a lot of interest and attention because they are having a spiritual experience.”

I dance another evening on a cement floor, accompanied by no bar. Almost all of the men wearing t-shirts. I arrive late. The Caja-girl complains lengthily on this point and still charges me full price. No time to waste, I sit in a prestigious spot. The guy at the next table to my left points imperiously at my bag and commands “shoes!” After our dance the guy at the next table to my right, a cross between Clint Eastwood and Wolverine (from the X-Men) stretches his neck toward me. “Are you in YouTube?”

After satisfying the curiosity of dancers with wide ranging skills who approach the stranger as they might a beginner –with a bow and outstretched hand– my feet are screaming. Really it’s not worth it to me to be outdoors if the surfaces are so unyielding. The third milonga, same kind of setting. This time I bring a bottle of Lambrusco. There being no water or cups provided, I drink from the bottle in my pre-planned and therefore unavoidably high-cleavage costume. I surrender to the image of “crazy girl”. At least I’m not wearing weird shoes!

The Italian men like to dance with me. After the dance they say “Brava!” a superlative I thought was reserved for opera singers, which I am overjoyed to receive. I respond with “Bravo!” Spread the love. Then another teetering trip back across the grass or gravel to a plastic chair, blinking under the flourescent lights, glad the Lambrusco is so gently carbonated. It’s really not easy to drink champagne from a bottle, but at least if it’s white your white dress is safe. Red champagne, by any name, is a dangerous proposition.

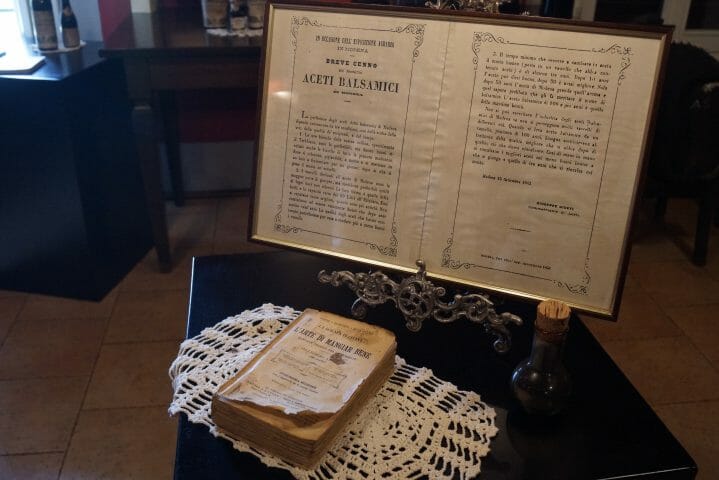

The last milonga sports the same LED lighting as my last restaurant. So top-rated (not only by bloggers but also by locals), that I squeeze a precious 30 minutes from the packing juggernaut (3 new pairs of shoes + kilos of cheese, salami, and balsamico, and delicate pastries already weary about the trip) to try one more time for epiphany, but end up advising another pair of American honeymooners not to be afraid of Lambrusco and that the tour of Giusti Balsamico is really well worth it for the smell alone. While I watch the waiter squeeze caramel sauce from a commercial plastic bottle onto my panna cotta.

Balsamico is made by a process of seasons: Fall: harvest the grapes, cook the juice to release the alcohol and crystallize the sugar. (This is “saba”, a great product on its own, which Nicholas Beckman taught me to dribble over a slice of Fuyu persimmon with a blanket of Burrata.)

Put the syrop in large chestnut barrels to ferment. In the winter, the fermentation stops. The spring bacteria enter the unsealed barrels to transform alcohol into acidity.

Denominazione d’Origine Protetta (DOP) Balsamico to be certified by the “consortium” (and receive its label and €10/ml price) must age for 25 years through a “battery”. Nevertheless no balsamic has an age, because the barrels are never emptied or cleaned. They still contain the sediment of hundreds of years. Giusti produces 250 l/year. A DOP-rejected batch may be resubmitted the following year.

Giusti also reserves their 50- and 100-year balsamicos for non-corsortium sale at €27 and €49/ml.

A battery contains 5-7 barrels of decreasing size. Each year the smallest barrel’s evaporation is replenished by the next largest barrel, who must also be made of a different kind of wood. The second barrel’s evaporation is replenished from the next largest, and so forth. The new “syrop” is only added to the largest barrel each year, and travels for 5-7 years through the different barrels and woods until it reaches the smallest.

The balsamico companies are also permitted to produce Indicazione Geografica Protetta (IGP) aceto, which is also inspected, but is permitted to include directly wine vinegar and the syrop aged together in only one barrel.

The DOP-destined batteries are kept in the attic of the house, with temperature and humidity entirely dictated by the season. The smell is so rich and sublime that it actually compares in intensity and pleasure with the taste. The IGP production is made in a modern temperature and humidity-controlled room, which has an entirely different smell.

The company may sell a range of such acetos with different ratios of sweet (syrop) to acid (wine vinegar), but my perception at the tasting is that it is the taste of wood which is missing from the IGP.

Sometimes, tradition is worth it.